27 Jul The Serpent Motif in Antique Jewelry

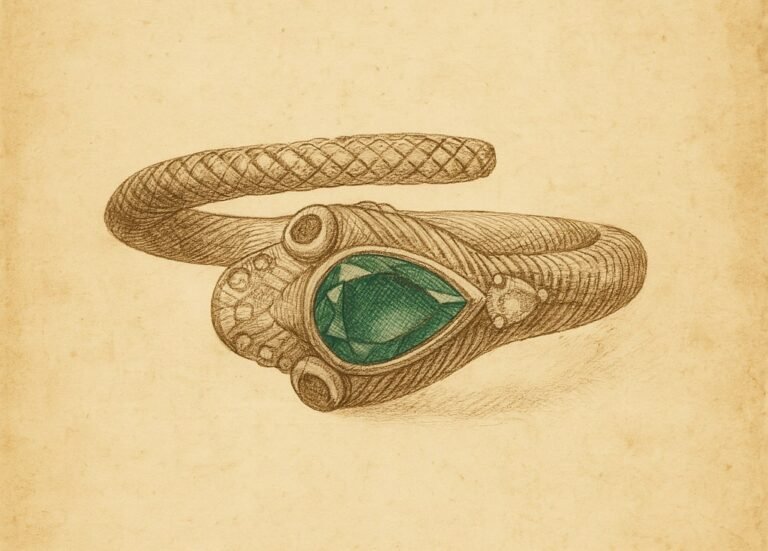

Seen Above: Ancient Egyptian Serpent Bracelets, Handcrafted in Gold in the 1st Century AD

The serpent has long held a central place in human culture — both feared and revered, associated with protection, transformation, eternity, and power. In the realm of jewelry, the motif has endured for thousands of years, shifting in form and meaning across civilizations and artistic movements. From its ancient ceremonial roles to its modern fashion interpretations, the serpent continues to serve as a powerful symbol — adaptable yet consistently evocative.

It is one of the many iconic motifs that you can use for inspiration when working with La Jolla jewelry designer Carl Blackburn to create a custom engagement ring or fine jewelry to commemorate a birthday, anniversary, or personal milestone. C. Blackburn Jewelers also buys and sells signed estate jewelry featuring serpent motifs.

Read on to discover why the serpent or snake jewelry has held such fascination for centuries.

Ancient Civilizations: Egypt, Greece, and Rome

The origins of serpent jewelry lie deep in antiquity. In Ancient Egypt, serpents were seen as divine guardians. The uraeus, a stylized upright cobra, was worn on the crowns of pharaohs to represent the goddess Wadjet, a symbol of royal authority and spiritual protection. Armlets, bracelets, and collars featuring snakes were common, typically crafted in gold and adorned with inlays of lapis lazuli, carnelian, or turquoise.

In Ancient Greece, serpents were associated with healing and immortality, particularly through the god Asclepius, whose staff entwined with a serpent remains a symbol of medicine today. Hellenistic jewelers produced highly naturalistic serpent designs — bracelets and rings that coiled realistically around the body, often with engraved scales and gemstone eyes. The motif was also connected with Hermes, Dionysus, and chthonic deities, blending themes of travel, fertility, and the underworld.

Roman interpretations of serpent jewelry emphasized both personal sentiment and technical complexity. Serpent rings, sometimes with multiple coils, were exchanged as tokens of love, fidelity, and mourning. Some pieces featured miniature compartments to hold portraits, locks of hair, or perfumes. Roman craftsmen often worked in high-karat gold, and serpent heads were frequently adorned with garnets, emeralds, or glass inlays.

Georgian Era (1714–1837): Sentiment and Symbol

The Georgian period valued deeply personal and symbolic jewelry. Though serpent motifs were less common than in later eras, they appeared in mourning rings, lover’s tokens, and memento mori — pieces meant to reflect impermanence and devotion.

Artisans of this time worked entirely by hand, producing intricate repoussé and chased goldwork. Serpent rings might encircle a finger with a single golden coil, sometimes incorporating secret compartments or engraved messages. These snakes represented eternal love, knowledge, or guardianship, and were often paired with other symbolic motifs such as hearts, urns, or skulls.

The intimacy of Georgian jewelry lies in its craftsmanship and meaning. Most pieces were commissioned and customized, and each serpent design from this era tends to reflect a specific relationship, loss, or emotional bond.

Victorian Era (1837–1901): Royal Revival

The Victorian era marked a turning point in the popularity of serpent jewelry. In 1839, Prince Albert presented Queen Victoria with a serpent-shaped engagement ring, featuring an emerald — her birthstone — set into the serpent’s head. This gesture, laden with symbolism, aligned the snake with themes of eternity, loyalty, and domestic devotion. It sparked a widespread fascination with snake motifs across Britain and Europe.

Throughout Victoria’s reign, the serpent appeared in a variety of forms — bracelets that coiled around the wrist, brooches with intertwining snakes, and rings where the serpent bites its tail, echoing the ancient ouroboros symbol. Artisans experimented with both naturalistic and stylized depictions, often using gemstone eyes, enamel detailing, and engraving to emphasize lifelike features.

During the era of mourning jewelry (particularly after Albert’s death in 1861), serpent motifs were adapted into somber, reflective pieces. Crafted in jet, onxy, or black enamel, these items often contained hair or miniature portraits and used the snake to symbolize continuity beyond death.

By the end of the century, the serpent had become one of the most recognizable motifs in British jewelry, favored for its layered meanings and visual impact.

Art Nouveau (1890–1910): Symbolism and Natural Forms

In contrast to Edwardian restraint, the Art Nouveau movement embraced fluidity, mysticism, and a return to natural inspiration. Jewelry became a medium for artistic expression, and the serpent — long associated with transformation and mystery — was a fitting subject.

Designers like René Lalique, Georges Fouquet, and Lucien Gaillard created visionary works that often combined the serpent with other organic elements: flowers, dragonflies, and female figures. Snakes entwined themselves around the necks of nymphs or emerged from blossoms, rendered in enamel, horn, opal, and moonstone. The use of plique-à-jour enamel allowed for stained-glass effects, adding to the ethereal quality of these designs.

Art Nouveau serpent jewelry often evoked mythological or psychological meanings — suggesting transformation, sensuality, or the merging of human and animal forms. These were not merely accessories but statements of symbolist art, worn by those aligned with avant-garde aesthetics and spiritual exploration.

Art Deco (1920s–1930s): Stylization and Modernity

The Art Deco period introduced a radical new vision: one of order, technology, and global influences. Designers drew inspiration from African, Asian, and particularly Egyptian sources — due in part to the 1922 excavation of King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

Serpent motifs reflected this cultural fusion. While retaining their historical significance, they were reinterpreted through the lens of geometric abstraction. Coiled snake bracelets, for example, featured repeating patterns, sharp angles, and stylized scales. Materials such as onyx, lapis, coral, and rock crystal were paired with white gold or platinum settings.

The cobra, in particular, enjoyed renewed popularity, appearing in necklaces, tiaras, and cigarette cases. These representations were sleek, symmetrical, and modern — more architectural than organic. While the serpent retained a certain symbolic weight, Art Deco design prioritized visual harmony, bold contrast, and precision.

Retro Era (1940s–1950s): Glamour and Reinvention

During World War II and its aftermath, jewelry design underwent another transformation. Restrictions on platinum led to an increased use of yellow and rose gold, while advances in engineering enabled more mechanical flexibility.

In this period, serpent jewelry returned to prominence in the form of statement pieces. Designers created bold coiled bracelets and necklaces using the Tubogas technique — a flexible, gas-pipe style chain that allowed for lifelike articulation. These designs were not only visually dramatic but also comfortable to wear, wrapping naturally around the wrist or neck.

Jewelry houses like Bulgari became especially associated with the serpent. Its Serpenti collection, launched in the 1940s, featured watches disguised as coiled snakes, with gemstone-studded heads that opened to reveal timepieces. These designs married ancient symbolism with Hollywood-era glamour, appealing to an international clientele.

The serpent in this context was a figure of bold elegance — associated not only with mysticism but with power, luxury, and sensuality.

Modern and Contemporary: Personal Expression

In the contemporary era, the serpent motif remains a staple of fine and artistic jewelry. Its adaptability continues to attract designers from across the spectrum — from established luxury houses to independent artists.

Bulgari’s Serpenti collection remains iconic, constantly evolving with new materials, colors, and modular forms. At the same time, designers like Gucci, Stephen Webster, and many emerging creators have reimagined the serpent in minimalist or avant-garde styles, working in materials as diverse as recycled gold, blackened silver, and lab-grown gems.

Symbolically, the serpent is once again viewed through multiple lenses: as a protector, a healer, a symbol of personal rebirth, or a reference to ancient cultures. Whether used in sleek, modern lines or vintage-inspired forms, the serpent adapts to the values and aesthetics of each wearer.

Today, it often appears in gender-neutral jewelry, tattoo-inspired engravings, and meditation-based designs, reflecting a wider cultural embrace of mythology, personal symbolism, and historical continuity.

Create a Custom Serpent Ring, Pendant, or Bracelet

Get in touch with San Diego jewelry designer Carl Blackburn to create an iconic serpent ring, pendant, or bracelet. Working from his boutique jewelry store in La Jolla, Carl welcomes the chance to work with you on creating a one-of-a-kind piece of heirloom quality jewelry, and always at a price that fits your budget. Call him at 858-251-3006 or send a text message to 619-723-8589.

You also can contact C. Blackburn Jewelers to sell antique serpent jewelry. Describe the piece you would like to sell in the contact from below. Or learn more by visiting the following link: San Diego Jewelry Buyers.